- Photo Safaris

- Alaska Bears & Puffins World's best Alaskan Coastal Brown Bear photo experience. Small group size, idyllic location, deluxe lodging, and Puffins!

- Participant Guestbook & Testimonials Candid Feedback from our participants over the years from our photo safaris, tours and workshops. We don't think there is any better way to evaluate a possible trip or workshop than to find out what others thought.

- Custom Photo Tours, Safaris and Personal Instruction Over the years we've found that many of our clients & friends want to participate in one of our trips but the dates we've scheduled just don't work for them or they'd like a customized trip for their family or friends.

- Myanmar (Burma) Photo Tour Myanmar (Burma) Photo Tour December 2017 -- with Angkor Wat option

- Reviews Go hands-on

- Camera Reviews Hands-on with our favorite cameras

- Lens reviews Lenses tested

- Photo Accessories Reviews Reviews of useful Photo and Camera Accessories of interest to our readers

- Useful Tools & Gadgets Handy tools and gadgets we've found useful or essential in our work and want to share with you.

- What's In My Camera Bag The gear David Cardinal shoots with in the field and recommends, including bags and tools, and why

- Articles About photography

- Getting Started Some photography basics

- Travel photography lesson 1: Learning your camera Top skills you should learn before heading off on a trip

- Choosing a Colorspace Picking the right colorspace is essential for a proper workflow. We walk you through your options.

- Understanding Dynamic Range Understanding Dynamic Range

- Landscape Photography Tips from Yosemite Landscape Photography, It's All About Contrast

- Introduction to Shooting Raw Introduction to Raw Files and Raw Conversion by Dave Ryan

- Using Curves by Mike Russell Using Curves

- Copyright Registration Made Easy Copyright Registration Made Easy

- Guide to Image Resizing A Photographers' Guide to Image Resizing

- CCD Cleaning by Moose Peterson CCD Cleaning by Moose Peterson

- Profiling Your Printer Profiling Your Printer

- White Balance by Moose Peterson White Balance -- Are You RGB Savvy by Moose Peterson

- Photo Tips and Techniques Quick tips and pro tricks and techniques to rapidly improve your photography

- News Photo industry and related news and reviews from around the Internet, including from dpreview and CNET

- Getting Started Some photography basics

- Resources On the web

- My Camera Bag--What I Shoot With and Why The photo gear, travel equipment, clothing, bags and accessories that I shoot with and use and why.

- Datacolor Experts Blog Color gurus, including our own David Cardinal

- Amazon Affiliate Purchases made through this link help support our site and cost you absolutely nothing. Give it a try!

- Forums User to user

- Think Tank Photo Bags Intelligently designed photo bags that I love & rely on!

- Rent Lenses & Cameras Borrowlenses does a great job of providing timely services at a great price.

- Travel Insurance With the high cost of trips and possibility of medical issues abroad trip insurance is a must for peace of mind for overseas trips in particular.

- Moose Peterson's Site There isn't much that Moose doesn't know about nature and wildlife photography. You can't learn from anyone better.

- Journeys Unforgettable Africa Journeys Unforgettable -- Awesome African safari organizers. Let them know we sent you!

- Agoda International discounted hotel booking through Agoda

- Cardinal Photo Products on Zazzle A fun selection of great gift products made from a few of our favorite images.

- David Tobie's Gallery Innovative & creative art from the guy who knows more about color than nearly anyone else

- Galleries Our favorite images

A Leica For The Rest of Us? The Sigma DP1X Reviewed and Field Tested

A Leica For The Rest of Us? The Sigma DP1X Reviewed and Field Tested

Submitted by David Cardinal on Thu, 02/17/2011 - 17:41

Even as a kid I knew enough to lust after a Leica. They represented the zenith of no compromise image quality. At first a Leica was way out of my budget so I didn’t think much about it. And then by the time I could seriously think about buying one I needed the breadth of a D-SLR system for my wildlife photography work. And with the price of the current Leica M9 digital rangefinder camera a cool $7,000 (plus thousands for each lens) I certainly wasn’t going to buy one just for fun. So I was excited when Sigma started producing small, rangefinder style cameras using the same Foveon sensors that they were using in their D-SLR. But the question was whether at 1/10th the price of a Leica I’d found a no compromise solution to high quality images in a small form factor. Read on to learn what I’ve found…

Even as a kid I knew enough to lust after a Leica. They represented the zenith of no compromise image quality. At first a Leica was way out of my budget so I didn’t think much about it. And then by the time I could seriously think about buying one I needed the breadth of a D-SLR system for my wildlife photography work. And with the price of the current Leica M9 digital rangefinder camera a cool $7,000 (plus thousands for each lens) I certainly wasn’t going to buy one just for fun. So I was excited when Sigma started producing small, rangefinder style cameras using the same Foveon sensors that they were using in their D-SLR. But the question was whether at 1/10th the price of a Leica I’d found a no compromise solution to high quality images in a small form factor. Read on to learn what I’ve found…

For Sigma Simpler is Better

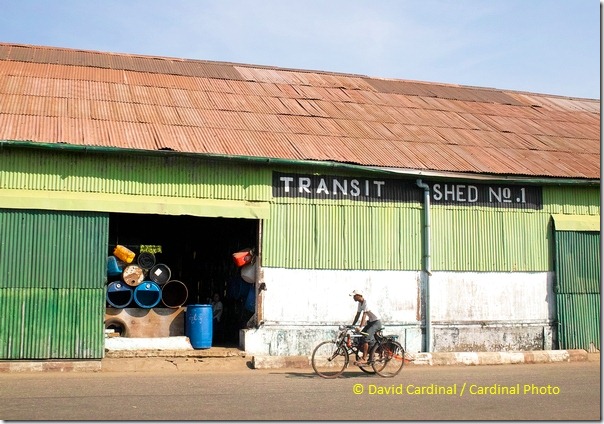

Like a Leica the Sigma DP1X is quiet, making it perfect for street shooting. And even though it is not as quick as a film camera can snap off the first shot or two more quickly than most point and shoots—although don’t rely on any heavy duty burst shooting especially in Raw mode.

Like a Leica the Sigma DP1X is quiet, making it perfect for street shooting. And even though it is not as quick as a film camera can snap off the first shot or two more quickly than most point and shoots—although don’t rely on any heavy duty burst shooting especially in Raw mode.

Even the Sigma DP1X feature set is just a simple upgrade from its popular and ground-breaking predecessor the DP1. Faster focus, better image quality and more streamlined controls are the big changes, addressing most of the usability issues users reported on the original.

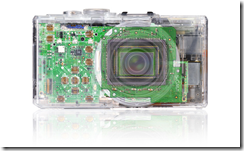

The Trick is the Foveon Sensor

The big difference between Sigma's cameras and everyone elses is their exclusive use of the Foveon sensor technology they acquired when they purchased the company. Unlike more traditional "Bayer Array" sensors which only collect one color (typically a mixture of Red, Green and Blue) at each photosite (or pixel) and then have to "de-mosaic" the three resulting "monochrome" images into a color image the Foveon X3 technology captures all three colors at each pixel. In exchange it has many less pixels--the DP1X is rated at 14MP by Sigma but that is actually a little less than 5 million 3-color pixels. The result is some amazing color fidelity and because there is no requirement for an anti-aliasing filter the apparent sharpness is also often more than the rated specs would lead you to believe. The downside has been the need for custom image processing software to correctly use the three color values (all three are not equally sensitive), but Sigma has come a long way in easing this issue.

Image Quality is Everything

To paraphrase, “the proof is in the image.” By having a prime lens and large sensor the Sigma compact cameras have focused all their effort on delivering stunning images compared to their peers in the compact camera category. And the DP1X delivers.

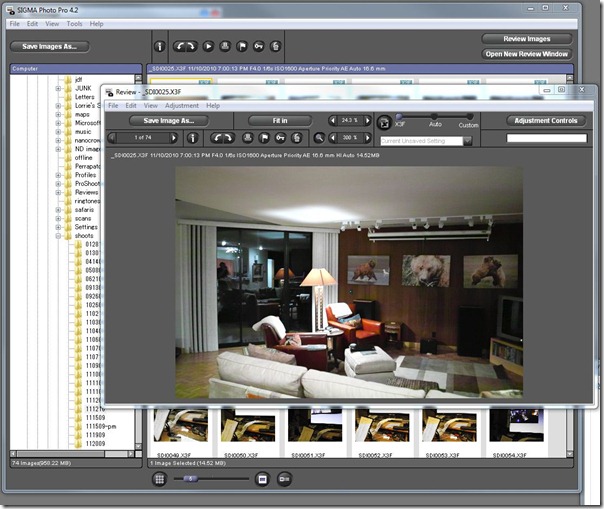

Sigma Photo Pro Software

Sigma’s software—the provided free application Sigma Photo Pro 4.2—is a mixed bag. The set of controls for adjusting images—especially Raw images—is very powerful but the image browsing and management framework around it is very pedestrian and not conducive to a high-performance workflow (as a simple example there is no way to turn off a persistent dialog that asks you to confirm every time you delete an image). There isn’t even any built-in routine for importing images from a card reader or for tagging images. Fortunately Adobe now supports the Sigma Raw (X3F) format in Photoshop and Lightroom so you can process Raw images from the DP1X the same way you would those from Canon, Nikon or Sony.

For most images the Camera Raw plug-in for Photoshop CS5 worked fine although for a few there was some problem which kept them from rendering correctly. As of my writing this it is still an annoyance but I’m sure it will get straightened out at some point.

The good news is that Sigma Photo Pro does a really excellent job of automated processing of tricky image like those taken in low light with high ISO. It comes out with sharp, low-noise results which are difficult to replicate in Photoshop. It’d be great to see its image processing functionality folded into Photoshop as a raw plug-in to combine the best of both worlds.

Convenient “Pro” Controls

By keeping the interface simple the camera becomes quick to use. D-SLR users will be familiar with the basic shooting modes: “A” for Aperture Priority, “S” for Shutter/Time Priority, “P” for Program Mode and “M” for Manual Exposure. Other settings like White Balance, ISO, Focus and Metering Mode can be set quickly using the “QS” button on the back and then using the arrow buttons to change options. Manual focus is accomplished simply by turning a small dial on the back of the camera rather than by fiddling with a ring on the lens. I don’t think I’d like that in a traditional D-SLR but for a point and shoot where your hands may be on each side of the camera while you look at the LCD I actually found it fairly convenient.

One non-standard choice Sigma has made is the flash sync speed of 1/30th of a second instead of the more traditional 1/60th. For a wide angle camera this might be a good decision since it is less susceptible to camera motion than one with a longer focal length and the choice of a slower shutter speed will tend to do a better job of letting the background image fill to complement the flashed image. Of course that makes this a good time to mention that the camera does not include any form of stabilization which while reasonable for a pro style rangefinder is certainly unusual for a compact camera in its price range these days.

One of the coolest features is a live histogram that reflects exactly what the camera is seeing, changing as you pan or adjust exposure settings.

Fixed Focal Length & Return of Depth of Field

The biggest compromise necessitated by the large sensor and drive for image quality above all else is focal length. The DP1 family—including the new flagship Sigma DP1X—features a fixed focal length of 16.6mm, equivalent to 28mm in 35mm terms. Their DP2 siblings (the DP2 and DP2S and the soon to be released DP2x) similarly have a fixed focal length of 24mm, equivalent to 41mm in terms of a standard 35mm camera. Your choice between the two camera families is mostly a decision about which focal length matches your shooting style. The DP1 family has a lot of appeal for landscape photography while the DP2 family may be more suited for people shots as it provides a more natural perspective for faces and indoor scenes.

One other great feature of the large sensor and f/4 lens is the ability of the DP1x to isolate a subject by blurring the background when shooting wide open. This ability is missing from most point and shoots as their tiny sensors make it very hard to create an image with a shallow depth of field.

What’s Missing

Before you rush off to order one of these unique cameras you need to think it through. The video capability is nowhere near up to the standard of cameras like the Canon Powershot G12 or Lumix series. It is only 320x240 resolution—only a fraction of HD resolution. And remember that it has no zoom. Fun for the days when you want to play Cartier-Bresson but a throwback if you are used to 3x, 4x or even 10x zooms. And the dozens of shooting modes that most point and shoots feature, along with fancy options like face detection are all missing. You’ve got a straightforward choice of basic operational modes (A, P, S, M for Aperture Priority, Program Mode, Shutter Priority and Manual Mode), auto and manual focus, evaluative or spot metering, and exposure and flash bracketing.

The DP1X does feature audio recording both in a clever mode that records audio automatically after each image—useful for repetitive recording of shot information—and a more traditional audio recording mode. The add-on viewfinder that fits in the hot shoe isn’t a nice as having an integrated version but at least its available for folks like me who rely on it.

The unique sensor of the DP family also seems to take a toll on the True II image processing chip. It is several seconds after an image is captured before the preview is displayed. In Raw mode it is then another few seconds before the image is written to the SD card, even with a fairly high-speed Class 10 card.

Field Testing

I’ve been bringing a Sigma DP1X along with me on various projects alongside my Nikon D-SLRs and my trusty little Canon Point and Shoot to see where and when it fit in to my workflow. What I found was a mixed bag. While less convenient than the Canon the full size sensor helped the Sigma DP1X take real “pro quality” images. That means they’re suitable for large prints and potentially stock sales (although I haven’t tried to sort out how the typical stock agency requirement of 10MP or 12MP views the radically differently structured Sigma/Foveon layered sensor).

However the Sigma wasn’t quick enough to really be a replacement for one of my D-SLRs as a “street” camera. Once it is shooting a burst of images it fires quite rapidly but it is noticeably slower than a D-SLR to take its first shot and it also pauses between shots unless you are firing a burst—in other words it functions like a point and shoot when it comes to speed. I love that it was smaller and less obvious but not being able to snap an image off instantly when I wanted to made it hard to capture those special moments that make street photography work.

- Log in to post comments